The High Lonesome Sound Roscoe Holcomb Singer/Songwriter 1965 Preview Editors’ Notes Though this album was released in 1965, Kentucky singer/banjo man Holcomb plays tunes that reach back to—and sometimes even predate—the earliest days of country and folk. His rough-edged tenor is a master marksman’s bullet tearing straight into the. Clip of Roscoe singing 'The Wandering Boy.' From The High Lonesome Sound (1963). Courtesy of John Cohen. Distributed through Berkeley Media LLC and Shanachie Entertainment 'John Cohen in Eastern Kentucky: Documentary Expression and the Image of Roscoe Halcomb During the Folk Revival,' a short video included in Scott L. Matthews' essay. This performance was recorded at Roscoe’s home in Kentucky in August 1962 while we were filing the High Lonesome Sound at his house. It is included here in preference to his New York studio.

Review by Carena Liptak

Paintings by Greg Dennie

Photographs by Carena Liptak

Compiled from three Folkways albums: 'The Music of Wade Ward & Roscoe Holcomb' (FA 2363), 'The High Lonesome Sound' (FA 2368), and 'Close To Home' (FA 2374). Recorded in 1961, 1964, and 1974. ℗ ©1998 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

—

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2455733-1285027873.jpeg.jpg)

Holding an original 1964 recording of Roscoe Holcomb’s The High Lonesome Sound feels like holding an artifact, un-earthed treasure, excitingly undiscovered and unspeakably rare. Because it’s music, ‘time machine’ might be a closer analogy. The album sounds like a sparsely attended concert: Holcomb plays and sings old-time mountain songs solo, supplemented only by guitar and fiddle, courtesy of New Lost City Ramblers members Mike Seeger and John Cohen, on one occasion. Without any editing or production, each of these tracks is a cohesive, sustained object, as pure and personal as a photograph.

The photographer—both literally and figuratively—is John Cohen, whose work with Holcomb began five years earlier, in 1959. In search of hard-time folk tunes to add to his band’s repertoire, Cohen traveled from New York City to eastern Kentucky. There, the mountainous countryside was a pocket of extreme economic depression—an anomaly, within what was otherwise a prosperous country—and home to a concentrated, rich musical tradition. You couldn’t throw a stone up in the air without it landing on the head of a musician, a saying went. With no narrower goal than to find music, Cohen wound up in the far-out hollow of Daisy. There, the people he met pointed him in the direction of Roscoe Holcomb and his banjo.

Hard times Cohen found. Holcomb, a former miner in his late forties, worked off and on in construction, general labor, and in his vegetable garden, but was often out of work due to poor health and bad times for getting a job. Singing and playing banjo did not mean as much to Holcomb as maintaining steady income, but Cohen immediately fell captive to his melancholy and utterly individual take on traditional mountain songs. He returned to Daisy several times in the sixties to record, interview and photograph Holcomb, eventually beginning to book him shows across the east and as far away as California. Many of these recorded performances eventually took their places on the track list of The High Lonesome Sound. Holcomb picked his banjo in an energetic, driving clawhammer style, switching out that instrument occasionally for guitar or, in a couple songs on this album, mouth harp. But The High Lonesome Sound was named for Roscoe Holcomb’s voice: a wavering, blues-infused tenor that stretched each line to its rhythmical limits, sometimes more instrument than human sound, sometimes melancholy as a train whistling echoing through a dark valley, and always touched with a powerful down-home lilt. For all its restlessness, the album plants us firmly in a place.

Haunted by the voice, I went to that place myself in August of 2012. Holcomb didn’t live there anymore; he’d died in 1981. His legacy has carried on, in the strangest imaginable way. Daisy, although exactly as hard to get to as Holcomb’s music is, has been the ambivalent object of many Cohen-esque pilgrimages over the years, including—fun fact—one made by Bob Dylan. I imagine everybody gets there kind of in their own way, because the unmarked narrow roads weave schizophrenically through the mountains, utterly unlocatable by even the most valiant GPS and liable to rebel against physical maps, too. I myself drove, for nearly an hour, maddening figure eights around the same closed gas station and the same white building marked “Faith Tabernacle,” recognizing it only by its marquee, kneeling deeply into a ditch, which read “We Are Too Blessed To Be Depressed.”

I stopped eventually outside a double-wide with a covered driveway and a dusty silver sedan with a couple of cats stretched asleep on its hood. A large red No Smoking—Oxygen In Use sign hung on the door. I knocked, figuring the resident to be old enough to have known Holcomb. A woman, old indeed, cracked the door skeptically. Once I stated my business, though, she lit up like Christmas. “You want to hear about Rossie?”

Though the trail looked pretty unblazed to me, I’ve since learned that pilgrims from the north knock regularly on these doors. Wanderers with notebooks and cameras come hunting for artifacts, for stories, for little gems of mountain authenticity, the way you’d buy an amber pendant with an insect trapped inside it in a museum gift shop. Locals don’t always take to these strangers kindly. You hear stories about mountain people greeting door-knockers like me with wrong directions, sending them to addresses of fictional old-time gurus by routes that, in fact, lead them back down to the highway and away from the mountain. This particular woman sat me down on a threadbare orange couch and told me stories about her childhood in Daisy, hearing the strains of Holcomb’s banjo coming from the porch of his house down the road in the evenings, and of his wife Ethel throwing a full bottle of pop at his head. The picture could have been a scene out of an old-time song, so closely it resembled the one I already knew, about the beloved folk singer in his community. Her story could be fictional, concocted out of years of travelers’ imaginations. Probably it was real. I was lucky; she could have shot me. It happens.

It happens because, since the fifties, eastern Kentucky has captivated the documentarian’s imagination. Due in part to the hillside’s inaccessibility, for decades people like John Cohen and I have been drawn to the glorious hills and hard times blues. Holcomb resounds with the kind of untameable authenticity that people fall in love with, but the crux of that authenticity may rest in its eternal murkiness. So we mine the culture for pieces of its music, coming at the neighborhoods in just the same way that coal companies come at the mountains.

It’s easy to see why we craved authenticity so fiercely. The folk revival was borne out of the fifties, a decade of radically escalating commercialism. This applied to music. Feel-good songs and smoother recording techniques, even in the second that they changed the landscape of American music, left listeners nostalgic for something rough and raw. The inconvenience of mountain tunes contributed to their allure, their rarity a beacon of secret, un-tampered with truth.

John Cohen sought authentic American music, and found it in Roscoe Holcomb. Holcomb was a pure folk artist, not only for the rich collection of songs he’d accumulated and the traditional banjo picking techniques he mastered, but also for his poverty, history, and singularity of vision. He cared little for rock and roll, except for songs bearing the heaviest influence from blues standards, and had learned to play from his family and neighbors before radio and television appeared as ubiquitously in Kentucky households as they did elsewhere in America. When, in interviews, Holcomb describes the place where he comes from as way back there in old Kentucky, he is referring to a time, not merely to a place. Holcomb’s songs are as surely rooted in a musical era as they are in the geographical location of Daisy, Kentucky.

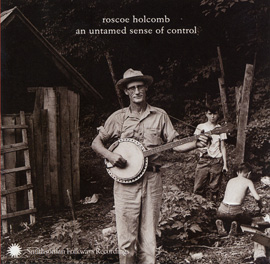

Holcomb, being a pure musician, did not see himself within a broader cultural context, and in fact never sought to release any records for national distribution at all, until meeting John Cohen. Cohen was necessarily tasked with the editing of Roscoe Holcomb. He decided which performances of which songs should appear on the records and what picture should be used for the album covers (including a choice that caused a stir—Holcomb appears on one record holding his banjo in front of a shed in his backyard, causing his wife to assume with alarm that the New Yorkers buying the album would believe that this one-room, rotted out structure was where her family lived). All of Cohen’s interviews had been taken from his own transcriptions, and were fact-checked and composed by him. His role as the sole spokesperson for Roscoe Holcomb, nationally known musician, weighed heavy on Cohen. Though the record is a faithful, loving portrait of the artist, The High Lonesome Sound could never have escaped some of John Cohen’s own projections of what an ideal old-time folk musician should be. Cohen was an old-time musician, too, and a problematic one: a wealthy, well-read and well-listened ethnomusicologist, he also worked as a professor and married into the Seeger family. He lacked Holcomb’s born authenticity, and through Holcomb, he must have hoped to find a soul connection to the music that he’d spent his life loving.

Roscoe Holcomb Youtube

That is why, when Cohen chooses the nine-minute recording of “Little Bessie” taped in Holcomb’s house, over the much-shorter New York City studio version, to close out the record, it’s difficult to say whether it was Holcomb or Cohen that put special emotional emphasis on that song. The album may well be put together in the spirit of imagined authenticity, not a musical project of Holcomb’s but an attempt at a photograph, by an admiring fellow artist, of Roscoe Holcomb in the early 1960s.

—

Roscoe Holcomb The High Lonesome Sound Rare

Carena Liptak writes for Turntable Magazine and The Music and Memory Project. She hopes to receive an M.F.A. in Nonfiction Writing from Columbia University’s School of the Arts and is currently working on a project about old-time music in eastern Kentucky.